Courage is an admirable virtue. There’s not much debate.

“It is not the critic who counts: not the man who points out how the strong man stumbles or where the doer of deeds could have done better.

The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena, whose face is marred by dust and sweat and blood, who strives valiantly, who errs and comes up short again and again, because there is no effort without error or shortcoming, but who knows the great enthusiasms, the great devotions, who spends himself in a worthy cause; who, at the best, knows, in the end, the triumph of high achievement, and who, at the worst, if he fails, at least he fails while daring greatly, so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid souls who knew neither victory nor defeat.”

—Theodore Roosevelt

Courage is a cornerstone of ancient myth and religion across every civilization on earth. Stories of Heros told and retold pre-date recorded history. In modern times our contemporary myths (films and television) continue this very human tradition with leading men and women overcoming impossible odds with confidence, style, and the inevitable one-liner. Storytelling, whether ancient or modern, resonates at a deep level. The unshakable archetypes of King, Warrior, Magician, and Lover dwell in an ancient interstice of our souls.

Philosophers have pondered what constitutes courage since antiquity. There is agreement that courage is persistence in the face of danger or hardship. Some areas of disagreement are what constitutes danger or hardship and the role of fear. Also, whether courage is learned or innate and if real courage necessarily involves selflessness. Does “fearless” really mean the absence of fear or someone who practices identifying fear as an additional obstacle and setting it aside?

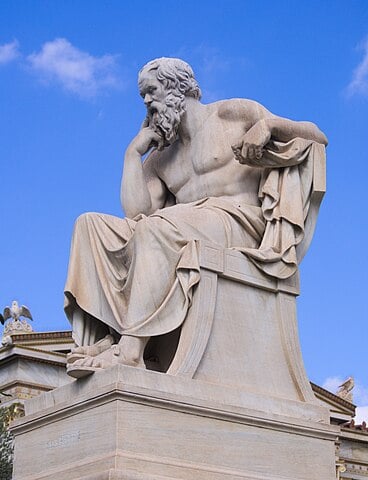

Latches by Plato

In Plato’s dialogue Latches, Socrates questions the nature of courage. Is it solely defined as the ability to remain steadfast in the face of danger? Or does it involve having knowledge and wisdom about what is truly worth risking one’s life for? Latches argues that courage is “the ability to withstand pain and fear” and that fighting courageously comes from within – that is, some men innately possess courage and some do not.

Nicias argues that courage should be defined as “knowledge of what is to be feared and what is not” and therefore that courage is learned. Socrates challenges the definition of courage as mere fearlessness. He asserts that courage in the face of fear is more valuable than fearlessness. He agrees that courage is not divorced from knowledge but says Nicias’ argument is too broad because knowledge of something is not the same as the experience of it. Socrates further argues that discerning when and how to act courageously requires wisdom – that true courage is not blind or impulsive.

Nicias argues that courage should be defined as “knowledge of what is to be feared and what is not” and therefore that courage is learned. Socrates challenges the definition of courage as mere fearlessness. He asserts that courage in the face of fear is more valuable than fearlessness. He agrees that courage is not divorced from knowledge but says Nicias’ argument is too broad because knowledge of something is not the same as the experience of it. Socrates further argues that discerning when and how to act courageously requires wisdom – that true courage is not blind or impulsive.

Socrates links courage to other moral values and contends that it does not exist on its own but within a larger framework.

In particular, he argues courage exists alongside the virtues of justice, temperament, and wisdom. He emphasizes the interdependency of these virtues and cultivating high character, of which courage is only a part. Socrates’ philosophy is thus wholistic and defines courage as the knowledge of what is good and bad, and the willingness to endure the bad in order to achieve the good.

The Spectrum of Courage

The big takeaway from Latches is Socrates’ argument that some types of courage are more valuable than others: Courage in the presence of fear is more valuable than without; courage in pursuit of other virtues is more valuable still. Although he doesn’t say it explicitly, Socrates is implying that courage exists on a spectrum. The answer to the question of whether courage is innate or learned is probably both – that is, it’s a spectrum and it’s not something possessed but is instead characterized by decision followed by action. Whatever the circumstances, fear must be overcome. The courageous person resists the temptation to relieve fear-driven discomfort through avoidance and faces the fearful situation.

Scared is what you’re feeling. Brave is what you’re doing. –Emma Donoghue

A more modern perspective according to psychologist Stanley J. Rachman (and expanding upon the work of Peter Lang)1, courage takes into account three components of fear: The subjective feeling of apprehension, the physiological reaction (increased heart rate, perspiration, etc.), and the behavioral response. If a person genuinely experiences no apprehension, no fear, and no potential personal consequences, then they have no skin in the game – their actions could hardly be courageous. It might be clever or virtuous, but not courageous because no courage is required.

Courage Springs From the Same Source as Self-Esteem

Psychologically, motivations for courage have some of the same roots as self-esteem: Self-efficacy, a strong support group, and past experience overcoming adversity. An expanded view would be confidence in the functioning of our minds, self-trust, belief in one’s ability to commit to and achieve a goal, acting in concert with others, and mastery of vicissitude. These boil down to the three catalysts of courage: Competence, confidence, and commitment.

Maya Angelou highlighted its importance when she said, “Courage is the most important of all the virtues because without courage you can’t practice any other virtue consistently.” For the alcoholic/addict, behaving courageously when wrapped in a blanket of dread and fear and dominated by perceived failure might seem a bit like putting on tights and a cape and pretending to have superpowers.

Given this, our ability to demonstrate honesty, perseverance, patience and all the other high-character virtues rest upon the foundation of courage. So we better pay attention if we are serious about improving our character and remaining sober. AA’s action steps (4,5,8,9) all require courage. It takes courage to honestly and objectively look at your faults, shortcomings and bad behavior. And it takes courage to openly talk about things you are deeply ashamed about. It takes courage to face yourself, warts and all. Courage is arguably the most important psychological tool at the recovering addict’s disposal.

They say that feelings are not facts – and in this case, the fact is that exceptional challenges (like stopping an addiction) are an opportunity to exercise exceptional courage and reap exceptional rewards. It’s where the rubber hits the road. As author C.S. Lewis said, “Courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of the virtue at the testing point.”

Exercising Courage is a Requisite for Developing Self-Esteem

Courage is the necessary starting place for the achievement of any personal change and growth. Growth does not happen in the comfort zone, it happens only at the edges. Pushing beyond the boundaries of what is comfortable is necessary to open up to new possibilities, build self-confidence and self-esteem, and move toward accomplishing goals. Courage is particularly important to building self-esteem, and there is a counter-intuitive (but obvious) reason: Courage as an action builds self-esteem regardless of outcome. You’ll feel better about yourself asking for that raise even if you don’t get it. You’ll feel better walking up to that girl and talking to her even if she rejects you.

“Growth and comfort do not coexist”

–Ginni Rometti

Courage is a Decision Followed by an Action, not a Possession

People don’t have courage, because it’s not something to have. It’s something done. Courage is not an ingredient; nor is it the entrée. Courage is the oven. It’s not a resource to reach for, any more than “amazing” is a spice on the shelf.

We assign the label courageous to people after they have demonstrated courage. When we ask the firefighter or the intervening bystander, “What gave you the courage to do that?” we give credence to the premise that something inspired the courageous act. Something incited the potential to act courageously, and it’s not courage. It’s something else. It’s intent. Intent encompasses the catalysts (competence, confidence, commitment) that ignite courage and project it forth into the world. Intent is the real target.

Action-Based Courage has its own Rewards

It’s worth mentioning again that the rewards of action-based courage are distinct from the outcome. One of the important principles embraced by Self Design Recovery is that all meaningful progress builds on failure. Failure can be frustrating and discouraging, but it is essential to reflect on what went wrong and develop perseverance. The key is to reframe failure as real-world learning. Winston Churchill said, “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm.”

Who possesses more experience, wisdom, and character, the man who fails repeatedly and after much effort, succeeds, or the man who experiences quick and easy success? Quick and easy success often leads to arrogance and hubris which usually leads to a reckoning. Others can, in fact, root and possibly contribute to the likely downfall – which will elicit a general feeling of schadenfreude.

But nothing happens, good or bad, without the courage to get in the game.

“The secret of life is this: When you hear the sound of cannons, run toward them.”

–Marcel France

Courage is Everyday and Everyone

American culture suggests courage is only present in grand, heroic examples from sports, military service, or crime-fighting. But in reality, courageous acts occur all around us in moments big and small. People across every age and walk of life step into moments of courage to remind us that it’s part of our everyday experience. And the people demonstrating courage are not superheroes, but regular folks.

A very partial list of everyday courage:

- Start something new

- Stop something old

- Speak the truth

- Remain quiet

- Be uncomfortable

- Confront

- Listen

- Own a mistake

- Take a risk

- Start over

- Go against the grain

- Take charge

- Sacrifice

- Overcome

- Change

If not all courage is grandiose, then let’s break down some types of courage, Western-style:

- Physical courage- The ability to act in the face of physical danger, pain, and difficulty.

- Social courage- The ability to take risks in social situations. The ability to speak up for yourself, even when you are afraid of judgment or rejection. Stepping out of one’s comfort zone. Speaking up and/or taking a leadership role in social situations.

- Emotional courage- The willingness to face and overcome emotional challenges such as loss, anxiety, and depression. It also involves being open about your feelings and emotions; a willingness to be vulnerable.

“Only those who risk going too far can possibly find out how far one can go.” –T. S. Eliot

- Moral courage- Standing up for what is right, even if it goes against the norm or is unpopular. Speaking out against injustice and refusing to participate in unethical practices.

- Intellectual courage- A willingness to challenge one’s own beliefs and be open to new ideas, perspectives, and interpretations. It can also involve questioning authority, changing the status quo, or taking risks in pursuit of knowledge and innovation.

Physical Courage

Physical courage is the variety that perhaps we are most familiar with. As a society, we hold military veterans and public servants like firefighters in high esteem because their work is necessarily dangerous and serves the greater good.

There are a large number of addicts who exhibit and exercise physical courage. Part of this is due to the fact that alcoholics are statistically more likely to be “sensation seekers”2 defined as the desire for adventure and excitement, the preference for unforeseeable situations and friends, and the willingness to take risks simply for the experience of living them. Many (but not all) addicts participate or have participated in contact sports and other dangerous recreational activities such as motorcycle racing, skate/snowboarding, skydiving, etc.

Alcoholics also occasionally reflect on the diminished value they place on their own lives – risking one’s life isn’t so difficult when one doesn’t particularly value it. Finally, physical courage is usually the least psychically painful type of courage to develop and some alcoholics substitute physical courage for lack of courage in other areas in an attempt to demonstrate to themselves (and others) that they are not cowardly. This is a type of machismo and is both foolish and denial-based. As a general rule, trying hard to impress is a huge mistake.

Social Courage

Developing social courage is a common source of struggle for alcoholics and addicts. Many of us started using drugs or alcohol because acceptance came so easily with the party crowd. We quickly discovered that alcohol and drugs made us more comfortable and confident in all manner of social situations. Many (but not all) alcoholics have an external locus of control which is a belief system attributing events, outcomes, and feelings to external sources.

This means that other people’s reactions control addicts’ feelings about themselves. Alcoholics use Alcohol and/or drugs to blunt the connection between others’ opinions of us and what we think about ourselves. For many addicts, this is a very welcome change – some alcoholics report that they never felt like they could truly be themselves until they discovered booze. Many report that the single best thing booze did for them was make them not care.

Fortunately, there are ample opportunities to practice social courage in everyday life, whether at the office or the coffee shop. One tip is whenever you are debating commenting or saying something to someone, just do it. The key is to do it immediately, not so much because you might talk yourself out of it, but because acting without hesitation is better practice – more courageous, more confident – and the person you are going to speak to will subconsciously pick up if you are hesitating. One observation about talking to strangers is that it is zero risk – what that person thinks about you is irrelevant. Other good low-risk situations are pick-up sports, the gym, and the subway/bus stop.

Twelve-step Meetings Are Fantastic Places to Practice Social Courage

Twelve-step meetings are also a prime practice ground for developing social courage. Opinions vary here, some people routinely share simply to develop the habit whether they have something to contribute or not. But it’s important to speak up when you have something interesting or important to say. Many people are petrified of public speaking, which itself is reason to do it, and it’s a valuable skill to practice.

Speaking up when what you have to say veers from the AA party line is particularly courageous and rewarding. Saying something controversial during a 12-step meeting, and doing so confidently, is a valuable exercise in courage. It’s also an opportunity to practice the confidence gambit of “going all in” rather than hedging your bets. If you’re reading the content on this site you’ll be at no loss for words in short order.

When practicing social courage, another useful attitude to develop is the habit of letting go of the outcome. For life in general, how things turn out is of much less concern than putting in maximum effort. One way to move towards outcome detachment is to completely drop any agenda. The goal is not to develop business contacts or get the cell of the pretty girl. If there is a goal other than the experience of doing it, it is to provide a positive experience for all parties with the interaction.

Emotional Courage

Emotional courage is acknowledging emotions and expressing them in a healthy way as opposed to suppressing and avoiding them. Practicing emotional courage has several benefits, one of which is it develops resiliency – which enables us to bounce back more quickly from setbacks. Another benefit is being more likely to be open and honest with others. Openness, when done appropriately, can lead to deeper and more meaningful relationships. Key to emotional courage is the concept of vulnerability, which is the willingness to express one’s true thoughts, feelings, and emotions despite potential uncertainties and risks.

The topics of social and emotional courage and the surprising value of vulnerability are of such importance to the recovering addict that they will be covered in more detail in a separate post. We will provide techniques and practices to develop these key habits.

Moral Courage

Moral courage is standing up for what you believe in even when it is difficult. The first step is to identify your beliefs and values. Only when you have a clear idea of your values can you align your behavior with them. Consistency between actions and values is the most succinct definition of integrity. Exercising moral courage means embracing a willingness to speak out against things that violate your values. It does not necessarily mean being confrontational or aggressive. Additionally, it means encouraging and supporting others when they speak out.

“If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. We need not wait to see what others do.”

–Mahatma Gandhi

Intellectual Courage

Intellectual courage encompasses open-mindedness and the willingness to challenge our pre-existing beliefs. It is engaging in critical thinking in regard to established norms, beliefs, and theories even in the face of opposition and potential backlash. Intellectual courage involves being receptive to new perspectives and information regardless of whether they align with pre-conceived ideas. This type of courage requires individuals to acknowledge gaps in knowledge, overcome the fear of being wrong, and be open to learning from others. Additionally, it combines the seemingly contradictory paths of seeing the world from a more humble mindset and expressing dissenting opinions even when they may be unpopular or go against prevailing beliefs.

Cultivating intellectual courage fosters critical thinking skills, creativity, and innovation. It encourages individuals to question assumptions, challenge the status quo, and explore new possibilities while engaging in respectful and constructive dialogue and to base arguments on sound evidence and reasoning.

When We’re Tested – The Mechanics of Acting Courageously

If courage is the testing point for our integrity and character, then taking appropriate courageous action is vital. This means we must cross the Decision-Action Gap (DAG). The full explanation of the Dreams to Reality process and Crossing the Decision-Action Gap are beyond the scope of this post, but we will summarize here:

Decision

The DAG represents the space between decision and action. The starting point of the DAG is decision. We have decided what we should do. At this stage, we’ve already wrestled with the benefits vs. drawbacks of the action, engaged in critical thinking, moral reasoning, examined our emotions, engaged our values, attempted to determine biases, etc., to reach the jumping-off point: In order to be who we’re committed to being, we should and must do this. This side of the DAG represents our promises/word (to ourselves and to others), our duty, and the voice of our conscience or intuitive compass about the right thing to do.

Action

The far side of the DAG is the successful execution of the decision. On this side, we are living out our identity in the moment. It’s the moment when we keep the promise, achieve the goal, accomplish upholding our values. Having reached the far side, we are one step closer to actualizing our authentic selves and bringing our true character to life. Note that we reap the benefits of execution regardless of outcome. We can fall short of our goals and still reap rewards. “Shoot for the moon. Even if you miss, you’ll land among the stars.” –Norman Vincent Peale.

Fear, Intent, and the Decision-Action Gap

Fear characterizes the gap that lies between. The catalysts of courage (competence, confidence, and commitment) serve to assist in successfully making the leap. These catalysts reflect our action-based intent to reach the far side of the DAG. The Crossing the Decision-Action Gap post referred to above will describe these concepts in detail.

This DAG exists in all parts of our lives. Sometimes the gap has moral components (i.e., this action is not as honest and honorable as I would like), sometimes it is performance-based (i.e., procrastination, previous experience struggling with a similar challenge, poor quality effort), and usually it is also fear-based (avoiding a difficult conversation, etc.) We definitely notice, and so do others, when the decision and action don’t line up, and our integrity, character, and reputation suffer as a result.

Boiled down, integrity is primarily about congruence. It’s consistently arriving on the far side of the DAG. We notice when others do not cross the DAG and are out of alignment or lacking integrity, and we adjust our perceptions accordingly. But self-alignment is paramount. If we violate the very values, commitments, and standards we know in our hearts we should uphold, we know instinctively that we’re not firing on all cylinders. However, getting to the far side of the DAG is not always easy – far from it. More shall be revealed.

One Final Thought:

Resting on your laurels – AKA complacency – is your enemy. Comfort is your enemy. Being comfortable in your own skin is not the goal. An ex-actor coworker once told me the most important thing he learned from acting was the value of getting comfortable with being uncomfortable. If you’re comfortable it’s time to set a new goal and do some courage. As a matter of fact, speak up at a meeting and say that.

“I’m fearless. I don’t complain. Even when horrible things happen to me, I go on.”

–Cardi B