In this post we explore the vital concept first introduced in the Courage post, the decision-action gap. In that post, we summarized the steps involved in putting a goal into action: Decision, intent, action. You can read the most relevant sections by clicking here: Courage is a Decision Followed by an Action and here: The Mechanics of Acting Courageously.

“Inaction breeds doubt and fear. Action breeds confidence and courage. If you want to conquer fear, do not sit home and think about it. Go out and get busy.”

– Dale Carnegie

Putting Goals and Decisions into Action

It bears repeating that courage is not something possessed but instead is something demonstrated through action. Courage is not what empowers us to take positive action – courage is the label we give it when it’s done. The what (our target) is Intent: That which animates courage and enables us to navigate what Dr. Kevin Basik has termed the Decision-Action Gap (DAG). Getting across the DAG is not a trivial matter. The inability to navigate the DAG consistently is one of the primary roadblocks to us creating the life we desire.

What is the Decision-Action Gap?

Man looks in the abyss, there’s nothing staring back at him. At that moment, man finds his character... – Hal Holbrook

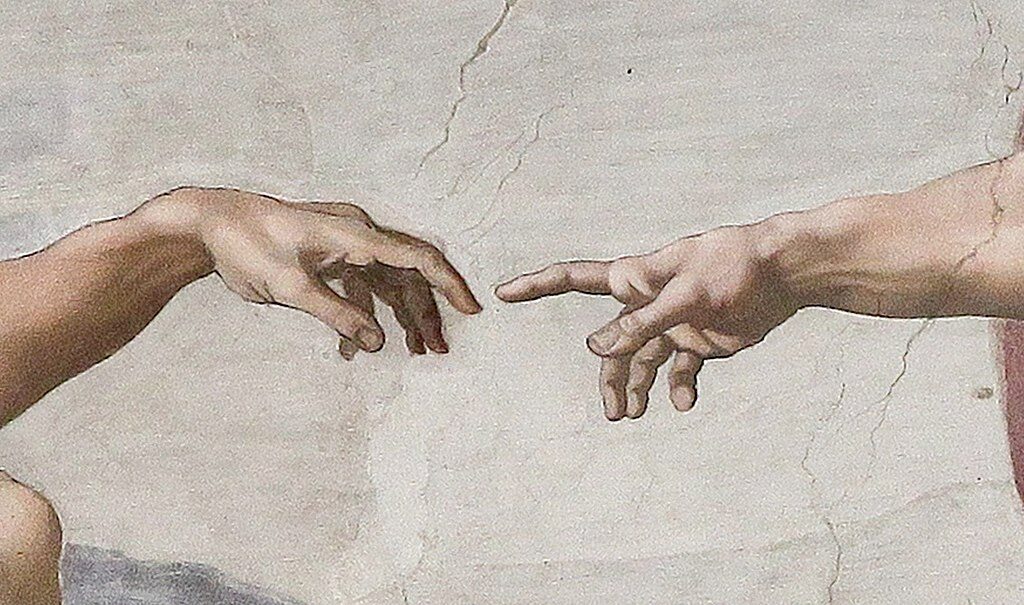

The decision-action gap constitutes the testing point of our character. The near side of the decision-action gap represents our decision to act. By this point, we have already engaged in the decision-making process, including intuition, critical thinking, biases, etc., and determined ‘I must do this thing.’ The near side of the decision-action gap is our promise (to ourselves or others), our word or duty, or our inner voice. Above all else, it is our obligation to ourselves to fulfill our decision. The far side of the gap represents us walking our talk and living our decisions. It is the promise kept, the obligation fulfilled. It is us living responsibly and bringing our authentic selves to life.

Our willingness and ability to cross the decision-action gap is adversely affected by obstacles standing in the way of action. Whether a particular obstacle is based on social norms, others’ expectations, logistical considerations, physical discomfort, or dysfunctional beliefs, each obstacle masquerades as a legitimate reason not to act. These psychological obstacles vary in power, from flimsy excuses to very real problems to overcome. But each has at least one emotional component and the potential to destroy our willingness to demonstrate integrity, discipline, and perseverance. Whatever the specifics of the obstacle, one element is almost always present: Fear.

Fear Reigns Over the Obstacle

When fear is ascendant, overcoming the obstacle becomes about courage. When we have clearly defined the problem and identified the issues, what remains is to fight through fear. We can distill fears at the decision-action gap into four categories:

- Fear of pain/discomfort/death: Most of us find ourselves drawn toward safety and comfort. Moving against the grain requires awareness of our tendencies and an act of will. Those who forge ahead and accept the necessity of risk earn the label courageous. When we tell ourselves, “I don’t feel like it” “This is going to be bad” or “I’m scared of doing this,” we’re giving voice to fear and our tendency to gravitate toward the easier, less difficult path.

“If you know the enemy and know yourself you need not fear the results of a hundred battles.” – Sun Tzu

- Fear of consequences: Possible physical, emotional, social, and professional consequences are the cause of many failures to cross the decision-action gap. We anticipate the impacts and costs of taking action, even if we base our anticipations solely in fear (especially if we base solely in fear). We must overcome this by accepting we cannot predict the future with absolute certainty and must accept the consequences, good and bad, of what we necessarily must do.

“Logical consequences are the scarecrows of fools and the beacons of wise men.” – Thomas Huxley

- Fear of the unknown: Other times are shrouded in ambiguity and uncertainty, and the consequences of our actions are unclear. When uncertainty dominates, further thought, reflection, and postponement are usually the most prudent course of action. However, outside events often drive us toward making a decision. Once we make a decision, fear of the unknown can cause us to freeze. By taking action, we let the chips fall where they may, accept the results, and make adjustments. We don’t allow fear of the unknown to frighten us into inaction when the situation requires action.

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown.” – H. P. Lovecraft

- Fear of loss: Prospect theory says that people evaluate potential gains and losses relative to what they regard as their status quo. Furthermore, it observes that individuals feel losses much more acutely than they value the equivalent gains. This tendency has far-reaching implications and is routinely used in advertising and sales (the ever-present “but this offer won’t last long”, etc.) Financial advisors are aware of this as well, pitching not just the value of returns but emphasizing that the market’s biggest gains occur in short time frames after a fall (“don’t miss out on the bounce-back!”) and the wisdom of staying in the market long-term.

- However, the fear of loss is not limited to the financial realm. It also includes loss of respect, friendships, employment status, property, and status with a valued group. When we don’t want to lose, our natural tendency is to not act. We must recognize when fear immobilizes us and use this awareness as motivation to act.

“Death is not the greatest loss in life. The greatest loss is what dies inside us while we live.” – Norman Cousins

Moving toward our goals is not about success, it’s about action

When we confront our fears and take action, we move to the far side of the decision-action gap, and have demonstrated courage. There are two important things to note: The first is that a particular result is not guaranteed. Success is not directly linked to courage, just action. Second, we reap the principal gains whether we are successful or not. All action in the face of fear, regardless of success, whether the end result is constructive or destructive toward our goals, increases self-esteem and experience.

The teenager looking for his first part-time job demonstrates courage by seeking employment despite repeated rejections for having no experience. The second-string quarterback demonstrates courage by stepping up to fill the shoes of the injured starter, regardless of whether or not he wins the game. Continued courageous action in defiance of setbacks is perseverance, which is one of the ingredients of mature masculinity.

“The greatest obstacle to being heroic is the doubt whether one may not be going to prove one’s self a fool; the truest heroism is to resist the doubt; and the profoundest wisdom, to know when it ought to be resisted, and when it be obeyed.”

– Nathaniel Hawthorne

Fear is subjective

It’s our perception of fear that matters – the obstacle’s difficulty is subjective. If one doesn’t experience fear and apprehension then the action isn’t courageous. If someone accidentally T-bones the getaway car of a bank robber, then the action is not courageous, it’s a freak occurrence (“What do you mean he robbed the bank?!”). Conversely, if someone perceives danger that doesn’t actually exist, and acts anyway then the person is still courageous (e.g., the bomb squad disarming a fake bomb).

These observations confirm a fundamental conclusion: Courage is not something we need to act. Instead, we define courage as acting despite fear. Acting in the face of fear IS courage. So the question becomes: What fosters and cultivates action? What strengthens and inspires courage and are the motivators to cross the decision-action gap?

Crossing the Decision-Action Gap: Intent

The answer is Intent. Intent is utilizing all of our personal resources in implementing a decision. These include our intellect, education, experience, conscience, intuition, critical thinking, and social connections to bridge the decision-action gap.

Intent, the way we define the word, is actively using our personal resources to shorten the jump, decrease the fear, and strengthen the leap. We can best describe it as setting ourselves up to make a successful leap or getting our ducks in a row before we jump. Thus, intent, like courage, is an action. It is taking the actions required to bridge the decision-action gap; it is our intention to cross the DAG by way of action.

“The man who is intent on making the most of his opportunities is too busy to bother about luck.”

– B. C. Forbes

The Frog on the Log

A secondary benefit of implementing decisions using intent is it prevents us from leaping off a cliff. We have all probably heard the story of the frog on a log when we were children. The log was the frog’s home, and it provided safety and comfort. The frog started to feel dissatisfied with his life on the log. He wondered what exploring the world beyond the pond would be like. The frog dreamt of adventures and new experiences.

So, one day, the frog weighed the advantages and disadvantages of leaving. Contemplating carefully whether leaving the log was the right thing to do, he consulted with some old-timer frog acquaintances. They encouraged him to jump because the decision to jump meant nothing unless he followed through. Acknowledging the wisdom and expertise of the log-sitters, he immediately jumped off the log and swam away, excited about what lay ahead.

However, as soon as the frog left the log, he realized he couldn’t swim for long distances. Without solid ground to rest on, he grew tired and started to struggle. He desperately tried to find another log or a safe place to rest, but it was too late. Exhausted and unable to find another log, the frog drowned in deep water.

Intent, when implemented properly, both empowers us to jump and ensures we do not drown.

We break intent down into three strategies: Competence, confidence, and commitment. These are the three catalysts of courage.

The Decision-Action Gap: Competence

Ask any of the emergency responders in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 how they were able to do what they did in the face of unimaginable stress (fear, dread, pain, fatigue, uncertainty, loss, limited resources), and they will likely very humbly say, “I was just doing what I was trained to do. I didn’t think about it.” But when you have no ability, plan, resources, experience, or tools fear will dominate your thinking. Conversely, the perception, however imperfect, of “I have a way through this. I can do this. Let’s go, time to execute everything I’ve practiced” helps explain why people take action despite extreme fear. Here are four elements that help us bolster our beliefs about ourselves:

Acquire the Tools

Focus on gaining competence in any skills required. We must determine the options available that we are capable of taking to learn as much as we can and get the vital experience. Through training, education, and learning from seasoned pros, we prepare ourselves to succeed at the decision-action gap. We must not hesitate to find a mentor who has had success where we intend to go, follow their guidance, and add their experience to our toolkit. Advice from experts, strategies, roadmaps, checklists, and even a change in lifestyle can make the counterintuitive obvious and transform a dream into a practical plan.

In this way, our mindset changes from “Can I do this?” to “How, exactly, do I do this?” and we reframe what was just a possibility into the subjective reality of a surefire win.

Focus On What’s In Front of Us

The decision-action gap can often feel insurmountable because we look at achieving the goal in one bite. As suggested in the goal-setting post, breaking big goals into a series of objectives and focusing on the objective in front of us prevents us from feeling overwhelmed. By breaking the challenge into the next doable step, we see how this objective leads to the next and so on. This requires us to mentally exchange the long-term struggle for the obstacle right in front of us and narrow our focus to what we control: the here and now. In this way, we build increasing competence and confidence with each obstacle we overcome.

Repetition and Muscle Memory

For the stand-up comic with 100 performances behind him, the idea of the next act is no longer nerve-racking, even if it’s for a large audience. With each rep, we add a notch to our confidence. Each time we act in the face of fear we build strength and stamina. With practice and perseverance, we stockpile muscle memory that enables us to more easily take courageous action and push through adversity. Everyday moments of risk-taking, truth-telling, commitment-keeping, and value-upholding creates the strength and fortitude to propel us toward our goals, allowing forward momentum to flow naturally.

Develop Communication Skills

The fear of public speaking, or glossophobia, is so common it might be considered normal. Up to 75% of people experience some level of anxiety and fear when speaking in front of a group. Another common communication issue is having difficult conversations in general. Whether the stumbling block is public speaking, selling an idea, asking for what we want, or delivering bad news, it pays to educate ourselves on how to communicate verbally effectively. Looking to other effective communicators for guidance is key. We can usually easily persuade peers and mentors to share their approach to similar situations.

Authors are also a valuable resource when faced with a commonly occurring challenge. For example, there are numerous books on how to effectively answer the most common job interview questions. By starting with “canned” responses, we can develop our own customized scripts that emphasize our strengths and downplay our shortcomings. Simply having options of realistic language serves as a starting place to practice delivery which serves to elevate competence and confidence.

Building competence alters our perception of the feasibility of crossing the decision-action gap – it may not be as far away as we initially thought. The size of the DAG is in the eye of the beholder.

The Decision-Action Gap: Confidence

As any skateboarder who has dropped in on a large vert ramp will tell you, when we think we can make the drop, we’re more likely to successfully execute, despite what our instincts about gravity are telling us. Fear is often based on worst-case narratives of disastrous outcomes and is fed by our insecurities. Doubts about ourselves and our abilities can paralyze us, even when we are competent at the task at hand. In moments like these, we need strategies to convince ourselves that, yes we can. We can pull the rabbit out of the hat and in make it happen. When we need to gain additional confidence to pull the trigger, we must keep several strategies at the forefront:

Build a Crew

Dispel any belief that real courage means we have to do everything alone. In fact, one of the most common factors of success is leaning on those in our social circles. In the documentary Arnold, Arnold Schwarzenegger cites his skill in team building as perhaps his greatest talent:

“I alone cannot accomplish anything. I need help..” “In that area of building a community, the talent of mine was actually better than my talent in bodybuilding..” “If you train together you help each other..” “That’s what you do, you help each other. Then before you go out you say ‘good luck’. Good luck, I’m going to beat you.”

Friends and family help us move toward our goals, but it’s the support and positivity those people provide to our psychology that matters the most. Their encouragement, shared concerns and commitments, strength, and sense of community help us feel like our actions are achievable. The effectiveness of accountability partners, coaches, and teammates is indisputable. When pressures overwhelm us, we can find strength and perspective through others and remain grounded in our commitment to our goals. Others remind us of what is possible for ourselves.

Take a Step Back

While catastrophizing a situation is surely debilitating, more commonly we exaggerate difficulties to a lesser extent. In either case, the fear is probably not entirely justified, and overcoming immediate issues is less difficult than we think. We can convince ourselves that our problems are dramatic and our particular case is unique. However, it is much more likely multitudes of people have faced dilemmas very similar to whatever the situation at hand. In fact, it may be pretty common, despite our initial reaction.

We can normalize challenges by recognizing that people constantly struggle with difficult issues. For example, holding people (and ourselves) accountable, discussing ethical concerns in a proactive and constructive manner, facing the temptation to make excuses for toxic people and organizations, struggling with fear, and hiring and firing (or being hired or fired) are part of life and leadership. By acknowledging that people constantly struggle with these tensions, we can feel encouraged that we, too, can navigate our way through. When we realize that others have overcome this challenge many times before, we can see that there is light at the end of the tunnel.

Acknowledge Previous Success

Confidence, in contrast with self-esteem, comes primarily from success. Self-esteem is primarily enhanced through exercising courage, but we gain confidence through achievement. By taking a moment to consider how the current situation compares to the ones in which we’ve previously succeeded, we can apply that confidence to the current task. By making this connection, we remind ourselves about our capabilities moving forward. We actively tell ourselves, “If you made it through that, you can make it through this. Let’s move.” Fear of competing for a corporate promotion is not exactly the same as competing for the starting position as high school quarterback, but there will be some similarities. Our skills, experience, and strengths may transfer to overcome this new challenge.

“You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face. You are able to say to yourself, ‘I lived through this horror. I can take the next thing that comes along.’”

– Eleanor Roosevelt

Take Advantage of Opportunities for Small Victories

Big obstacles are not as difficult after successfully completing a series of smaller ones. This stage-based strategy is commonplace in many forms of training, from rock climbing to scuba diving. After basic lectures and study, students work their way up (or down) a series of increasingly difficult real-world challenges. It’s a strategy we can employ in our everyday lives by saying ‘yes’ instead of ‘no’ to opportunities that pop up that are marginally scary.

Never ridden a skimboard at the beach? Worried if it stops suddenly you might fall headfirst into the sand? You’re right. You will. And if that happens, then you get up and do it again. Then you gradually work your way into riding into the surf. You get the idea. By forming the habit of conquering life’s little challenges, we prepare ourselves to face the big ones.

See Yourself in Others

It’s easier to believe you can do something if someone just like you has done it. Look for people who have met the challenge you are now facing, and look closely for the similarities rather than the differences. Sometimes the best tip someone can provide is to simply follow their example. Just seeing success can boost confidence as we confront similar fears. Mahatma Gandhi gave activists an example of what is possible when people act conscientiously and courageously. Robert Downey Jr. demonstrated being a superhero both on and off screen by overcoming a brutal addiction. Whether it is transforming the world or ourselves, others can inspire us because they remind us of what is possible.

The Leap of Faith

“I don’t believe in God.” – Edmund Dantes

“That is no matter, Edmund, for God believes in you.” – Priest Faria

– The Count of Monte Cristo by Alexandre Dumas

Sometimes in life’s journey, it’s necessary to leap when the long-term consequences of not leaping are unacceptable. Like leaving an abusive marriage or toxic job, we may not know what the next chapter may bring. And there are cases where we are proceeding toward a dead end and the new path is risky and requires sacrifice. Our choice could be between continuing a warehouse job that allows us to comfortably meet our financial commitments versus an opportunity in a creative field in line with our life goals that will initially entail a significant pay cut. Answering our true calling and living an authentic life often requires a leap of faith.

There are always going to be difficult choices involving things we can’t control. Whether or not the current leap is a leap of faith or a leap of the more run-of-the-mill variety, having unshakable faith that things will work out, a bone-deep knowledge that we will adapt and overcome, gives us the confidence to do what, deep down, we know we need to do.

Building confidence is about reducing fear. When it comes to crossing the decision-action gap, confidence and fear are opposite poles of the spectrum. More confidence equates to less fear. It’s as simple as that.

The Decision-Action Gap: Commitment

Commitment is the nature of the relationship we create with our goal. It is the desire and connection we have to the outcome we intend the goal to produce. Commitment is how we connect the here and now to what matters to us; it is the relationship between the present and the values that drive us. It is the thing that compels us to sacrifice our time and effort now for something we feel is absolutely worth it in the future.

“You always have two choices: Your commitment versus your fear.”

– Sammy Davis, Jr.

When other elements of Intent are low, the smoldering fire of commitment can drive action through the heart of fear. The following are some practical guidelines to strengthen our commitment:

Clarify Values and Identity

Unless there is clarity on who we are – what we stand for – we will have difficulty weathering the storms that are sure to come as we move toward our goals. We must clarify what values and virtues we commit to because these are intimately entwined with our life purpose.

Specificity matters. Broad, vaguely stated values can be less than useless because they can be twisted to translate to almost anything in practice. We must get specific about what we want to fight for. This is a case where our emotions are prominent – when the test of our integrity arrives, we must be firing on all emotional cylinders to meet the challenge. We’ve got to know in our hearts who we are.

We must redevelop our atrophied values

For the recovering alcoholic/addict, often we are not fully conscious of the specifics of what we want to stand for. We have a vague idea, but that is often not enough. On the other hand, we’re often keenly aware of what we DON’T want to stand for. One way to distinguish some positive specifics is to look more closely at these negative values to draw out some positive ones.

Honesty is one such example. We know we don’t want to be dishonest, but what exactly does honesty look like when put into practice? Or often we know we don’t want to be low-class, but what do style, grace, and polish look like for us? Is it a merely a professional presentation, or something greater? These are not academic questions. They translate directly into our evolving identity, who we want to be.

Guilt and shame are great motivators. It is healthy for us to want to be better and regret being less than we could have been. We’re often our own worst critic, and we can put those negative emotions to good use by clarifying the positive things we stand for.

Clarify Boundary Limits

We should make a conscious effort to define ourselves by what we stand for rather than what we stand against. That being said, it is also important to understand our boundaries – specifically our limits – what, in ourselves and others, are values, attitudes, low standards, crude language, biases, excuses, and behavior that are inconsistent with who we want to be and what we want to accomplish.

We focus this process on identifying who we want to be and avoid rationalizations inconsistent with what we are pursuing. When we accept second-class thinking from ourselves or others, we embrace the very mindsets that lead us to fail at the decision-action gap. “That’s good enough” is usually not good enough. “No one’s going to know” is untrue because WE know. Defining our limits strengthens our boundaries about what is and is out of integrity.

Stay in Touch with What’s Important

Sometimes we can become confused about our priorities when events are moving fast and life is fully in session. When we’re hustling, we can lose ourselves in the noise of phone calls, text messages, e-mails, and other’s expectations and demands and forget the values that brought us to this point in the first place.

When we quiet the noise and calm the distractions, we are able to see that the decisions we are making right now are directly tied to our values and goals. The feeling that we are too busy to further tap our mental bandwidth in aligning with our values is a dangerous illusion. Stressful times are another variation on the test of our character. We’ve all been distracted at moments when we should have modeled high character but instead took the shortcut, told the lie, or simply took the easier, softer, lazier way.

Often what keeps us on target with upholding our integrity is the realization that what we do affects everyone around us. Others can serve to remind us of what is actually important.

Define Your Crew

It is the verdict of the ages that who we are is largely defined by the values of those we stand with. Building a crew and a world around us who share a commitment to the values and goals we pursue can create a fortitude juggernaut where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. As social creatures, when we value membership in a group, we model behaviors that increase our station in the tribe’s social hierarchy. In other words, we change our behaviors to align with the values of the group.

That being the case, we would be wise to seek out or build a crew whose members understand the value of walking their talk. Construct a tribe that values courage as an action.

Share your Goals

When we communicate to others what goals we’re in the process of constructing, we create an accountability mechanism. Our goal becomes more real when shared. There is not only peer pressure but positive expectations we have about ourselves to not be a quitter and make good on our word. Also, we invite others to help us reach our goals. In turn, when we hear others’ commitments, we may be able to impart our experience to assist them in confronting and overcoming the problems they’re facing. And finally, sharing goals and commitments reminds us of what our priorities are. Sharing with others deepens and reinforces our commitment to reach goals on our terms.

“The only limit to your impact is your imagination and commitment.”

– Tony Robbins

Commitment is about strengthening our perseverance in the face of adversity. When we face strong headwinds in pursuit of our goal, commitment is our mental Clydesdale that plows ahead.

Dreams to Reality in Film

The 2023 film A Million Miles Away starring Michael Peña as migrant farm worker turned astronaut José Hernández animates many of the principles in the Dreams to Reality Series, including crossing the decision-action gap. [spoiler alert]

The film begins with José’s father Salvador imparting to young José his philosophy of life:

- Know what you want

- Know where you are standing – How far you are (from your goal)

- How you’re going to get there – Draw a roadmap

- If you don’t know how, learn

- When you think you’ve made it, you probably have to work harder

While José has embraced his dream of being an astronaut when still a child, it took him over a decade to fully transform his dream into a goal with any realistic chance of success. He does, however, initially make good decisions that start moving him in the right direction. He performs well in school, achieves a degree in electrical engineering, and starts working at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory.

A Dream is not a Goal until a Decision is Made

We learn that he has applied to, and been rejected by, NASA’s astronaut training program several times. At this point, we could say that José’s dream is still just that – a dream. He has not taken the steps required to transform his dream into a realistic goal. In other words, he has skipped the Intent phase and moved directly into the Action phase.

His supervisor, Clint Logan (played by Eric Johnson), provides a hint of what’s actually necessary when he tells José that an opportunity has opened up as a nuclear disarmament transparency observer in Siberia. Clint says this would look good on José’s NASA application. However, José does not immediately take the position.

José’s lack of commitment comes to a head when his wife Adela (played by Rosa Salazar) confronts him after discovering his numerous rejection letters from NASA. While initially angry over his hiding his ambition to be an astronaut, she asks some pointed questions that begin the process of bringing his dream to life.

In response to her initial anger, José attempts to explain away his ambition by saying “I just thought I should give it a shot” and “It’s a stupid dream”. She responds with, “What’s a stupid dream, the dream of sharing with your partner?” He responds by proclaiming “It’s never going to happen” and she asks “What if it did?”

The Cry of the Boy

José then asks, “why can’t you just be proud of me?” This reaction is important because we can interpret it as, “why can’t you just not confront me?” (“just leave me alone!” is the cry of the boy, not the mature man).

The key dialogue follows. Adela is proud of him for becoming a great engineer because that is a goal that he set out for himself, worked at, and accomplished. She is angry because he has a dream that he has not shared with her (the key member of “his crew”) and is selling himself short.

When Adela asked, “What if it did [happen]?”, she refused to accept his assertion that the idea is silly and tells him it’s not stupid to apply. She then asks the big question: “The people that got in, what do they have that you don’t?” José replies that, they have numerous skills and acquiring these skills takes money. The implication here is that he is fearful of going all-in and spending the money, time, and effort because in all likelihood he still will fail. Fear rules the obstacle. He became paralyzed at the decision-action gap, and his futile applications are an attempt to convince himself he’s actually pursuing his dream.

The Dream becomes a Goal

José finally gets serious; that is, he makes a decision. Astronauts are scientists, engineers, teachers. They have high-powered skills and hobbies. Astronauts are pilots and scuba divers. They are athletes and speak foreign languages.

Embracing Intent

José begins taking real action. He starts to move toward getting his pilot’s license and scuba certification. He starts teaching at work and begins physical exercise regularly. José eventually takes the job in Siberia to learn Russian. He shares his goal with his family and co-workers. At this point José could finally say he intends to be an astronaut; it’s no longer a dream.

José’s demonstrates his commitment by hand-delivering his latest NASA application personally to astronaut Rick Sturckow (played by Garret Dillahunt) and makes his pitch:

“Over the last ten years, every academic, professional, and personal decision I’ve made with the space program in mind. I earned a master’s in electrical engineering, earned a pilot’s license with over 900 hours of flight time, got my scuba diving certification, finished the San Francisco marathon, and learned Russian while traveling to Siberia as part of the transparency program of the Department of Energy.”

Into Action

José would not take no for an answer. He is accepted into the program; he has crossed the decision-action gap and is now fully in action. José discovers a new team completely aligned with his goals, overcomes enormous adversity during the training program, and finally earns his seat on a space shuttle. As fellow astronaut Kalpena Chawla observed, “Tenacity is a superpower.”

The Decision-Action Gap Summary

We realize our goals in three phases: Decision, Intension, Action. The obvious counterintuitive is that the majority of the work takes place in the first two phases. The intent step comprises the actions that set us up for success. It serves to bridge the decision-action gap, which is primarily characterized by fear. Intent also has three parts: Competence, which changes our perception of the size of the DAG, confidence, which reduces fear, and commitment, which powers us through. The steps outlined here supercharge our intent, make our hearts pump faster, and inject nitro into our leap. When the time comes, we make the vault across and onward to our dreams, realized.

Author’s Note: This post is based on The Courage Myth: 3 Catalysts to Strengthen the Master Virtue by Dr. Kevin Basik. You can read the original article here which includes additional sections on ‘Creating a Courageous Culture’.